Two Paths, One Like Mind: Unsettling Place-Based Education

This blog is based on the ideas that emerged through collaboration between four educators -- myself, Judy Dow, Marie Vea, and Emily Hoyler -- for the Decolonizing Place-Based Education workshop.

This is a Two Row Wampum belt. If you haven’t seen one before, Wampum belts are beautiful, intricate works of art; each bead is handcrafted from purple and white quahog shells and strung on sinew and leather. Behind these rows of beads is a centuries-old idea of walking two paths with one like mind, a concept that can help inform our work as place-based educators today.

A vision for peace and respect

The Two Row Wampum treaty, made in 1613 between the Onkwehonweh of Turtle Island (the original people of North America) and European immigrants, outlined a vision for peace and respect. In the context of the treaty, the belt’s two purple rows symbolize the paths of two nations moving side-by-side.

The idea still resonates. The belt pictured here was handmade by Judy Dow (Winooski Abenaki), educator and frequent collaborator of Shelburne Farms, who was commissioned to create the belt as a thank-you gift to none other than musician and activist Neil Young. As Dow describes, Young held a series of concerts to benefit the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation in 2014, which spent millions in legal fees to fight oil sands development. “The Athabasca and Young were of like mind that the tar sands coming onto Indigenous reservation lands was bad. Young fought the developers with his music, and the Athabasca fought with lawyers,” Dow explains. In that way, Young and the Athabasca walked two paths, with one shared goal.

Stories of walking two paths with one like mind can be found in everyday life. “For example, we may both have a like mind in agreeing we have a climate change issue, but how we might solve it is different,” says Dow. “Teachers and students are always learning at the same time. In that respect, they’re walking down different paths with like minds. This concept is all about learning.”

A multitude of pathways to learning

Contemporary, mainstream schooling often feels as though all learners and teachers are traveling on a single path of white dominant culture. The outcomes of this single pathway through the education system are predictable: a few will succeed, many will struggle, and some will be left behind. Additionally, the roots of the so-called traditional American education system stem from an extractive relationship to place and land, a relationship based on land theft, ownership, objectification, and resource management.

If we were to imagine schooling as a transformational space, a living process of intricate, interdependent connections, what might the outcomes for the land and our individual and collective selves be? If we aimed to create a 13-year learning journey in which we each could, as Tema Okun writes, “appropriately be in one’s majesty, and share in each other’s cultural bounty,” what would that look, sound, and feel like?

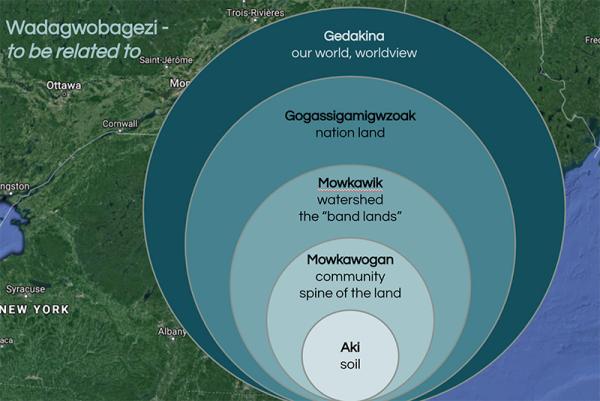

If we reference maps, learning standards, and other representations of geography, they underscore a separation of people from land, and a separation of experience from knowing. Maps carve out pieces of land claimed by one person or another, and demarcate the artificial separation of groups despite the continuity of the natural world. Commonly used science standards highlight human dependence on, and extraction of, natural resources from the land, describing this dynamic as a one-way, human-centric transaction. Bringing in the diverse experiences of personal connection to place, and the vast multi-generational knowledge of living in relationship with the land, adds dimensions that go beyond those structures. This graphic of Wadagwobagezi (above), developed by Judy Dow, illustrates the interdependent layers of relatedness for all of us who exist within Gedakina, “our world,” from an Abenaki perspective. It pushes us to consider a vision and practice of learning and living centered on relationships and reciprocity.

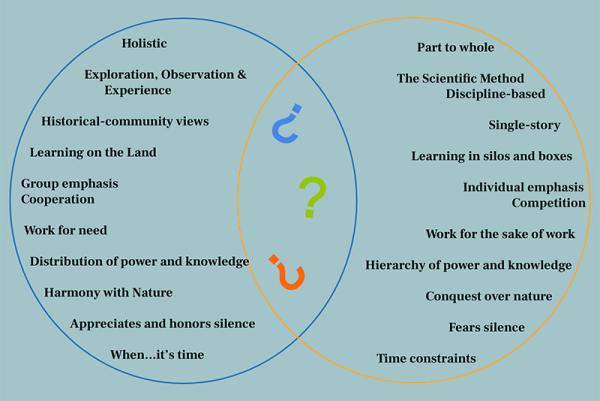

If we interrogate what we mean by education, specifically, the practices that teachers and learners engage in at school, what do we see? The structures that commonly dominate schooling today include rigid time schedules, single measures of achievement, learning in silos, and an emphasis on the individual. Leaning on the wisdom of the Two Row Wampum, we understand that there are a multitude of pathways to learning, and that honoring at least two of them is possible.

This Venn diagram (above) of “Learning in Two Vessels” holds some of the characteristics of traditional school-based experience and of traditional ecological learning, with the potential for connections across difference. As educators, learners, and community members, how might we inspire a multitude of pathways and inspire the well-being of all?

Final questions

A deep examination of how we do school, the underlying structures that support and restrain how teaching and learning happens, and our visions for something healthier open up a world of wonderful questions, questions that invite all of us to envision and create teaching and learning practices that transform the relationships between self, Land, and community for the benefit of all.

As you unsettle your approach to place-based education, ask yourself the following:

- What would happen if we, as a community, held Land as kin?

- What are the values that shape the river of learning, the shared space where a diverse community of learners travels?

- What would school look, feel, and sound like if we centered these values?

- What can I do today to learn within and across difference?

- What future do we want to be creating right now?

See our calendar for upcoming events and educator workshops.